Before someone tells me “it’s just ‘Waffle House’, there is no ‘the’ before the name,” I would like to state very clearly that I do not care. I do not care that including the article before the name of this dining establishment makes one sound like a backwoods hick. There are many names that, if preceded by an unnecessary “the,” will make the speaker sound uneducated or at least painfully colloquial in their speech. “The Walmart” and “the Winn-Dixie” come to mind as good examples of this linguistic marker that supposedly signifies a lack of intelligence or worldliness. However, there are many places and names that do not trigger this judgment. The Louvre, the Coliseum, the Sistine Chapel. These places are singular, known by only one name. There is only one of each, they have earned their distinction by article. You may protest that there are many waffle houses, and you’d be correct. There are many iterations of The Waffle House. They number in the thousands, and yet somehow they are one.

On the days I go to The Waffle House, it is somehow never sunny. The weather is always dreary. Clouds hang overhead, only allowing brightness through if diffused and grayed by their presence. Above the wet shine of the asphalt parking lot, the sign glows the yellowest yellow anyone’s ever seen, as primary as any kindergarten color chart yellow, the most archetypal version of the color there ever was. It gleams like the sun God forgot to flip on that morning before leaving the house.

No matter the hour, there are always several vehicles in the parking lot of the Waffle House. There may be a luxury car or two, but the majority are no doubt jalopies, beaters, and the oft-described-but-rarely-seen hoopties. Without fail, someone will be outside smoking a cigarette. They may be standing whilst speaking on the phone, perhaps seated on the curb looking at a screen. Every once in awhile the smoker will be exhaling their clouds of poor man’s SSRIs toward a sunset. Certainly though, no matter their difference in trappings, there will always be a smoker.

Once through the first door of the airlock and upon opening the second, the scent of the Waffle House is appropriately singular even in its variety. Depending on what currently occupies the griddle, one will be greeted by the scent of pork sizzling in its own fat, though it could be a number of cuts. Perhaps strips of bacon are crinkling their shrinking selves into the salted ribbons of a child’s breakfast. Perhaps a slab of Virginia ham is popping (with great threats of hot oil droplets slung onto the skin) and browning to feed the cook that will be eating in the back. Above the lower notes of salted meat comes the smell of some cleaner swabbed over a surface in between its uses. (The Waffle House never closes, so it must be cleaned in tandem with its services as an eatery.) Still above the chemicals wafts the smell of tea being brewed, and likely the sweetness of the sugar being dumped into the concoction. The Waffle House smells like the perfect 6:45 a.m. kitchens of America in the 1950s, one that existed in reality for a precious few and for the rest only in the brushstrokes of Norman Rockwell.

There is never a good spot to sit. The bar no doubt seats one if not two truckers, so spaced that one cannot pick a stool without being too close to one of them. There is never a seat where one can split the difference, either. So spaced, too, will be the couples, families, or singles in booths. There is seemingly no good time to appear at the Waffle House to ensure decent seating. Inevitably one will take a booth at the end, and the sun will be in their eyes. It is just the way of things, the price of admission. In a way, this is an engineering marvel. “Like it or lump it,” says the architect of the first and all other waffle houses, and all in the design. One imagines that as he took to the drafting desk, the memories of the railroad dining car that undoubtedly had affected him so much as a child dancing in his eyes, he thought, “This shall be my magnum opus.” So brilliantly did he design the Waffle House that it lives as a shining recreation of that original inspiration despite having never been able to roll along anywhere. Like the life-size Ark built in Missouri by Christian zealots, it is a replica so great it has succeeded in transcending its inspiration. Now it stands as a replica painfully American in its stubborn refusal to make the ideal workable, in its obstinate adherence to the absolute, no matter how foolhardy.

Once seated, no matter how uncomfortably, patrons will be greeted by a waitress. Dressed in an outfit that is not flattering and has not been updated since perhaps the mid 1990s, she is somehow elegant. The waitress will have so many buttons and pins on her apron that it has long since trespassed into the territory of tacky, but somehow it only seems to add to her charm. She is always kind, always pleased to see you. She is usually older than 60, almost certainly over 40. She will call you by any number of endearing platitudes, but none will ever arrive to your ear in a cloying key or with even a twang of falseness. She will grin in such a way that one imagines her face as lit from within. The expression will be shameless (perhaps even bawdy) in it’s exuberance, earnestness, and lived-in-edness. This smile is so unanimous amongst the waitresses that one wonders if the job postings must read “Mona Lisas need not apply”. These women, who have no doubt lived difficult lives marred by and married to trial and tribulation, seem unbattered and unbruised. They are steely in their assuredness that today can be a good day. Their optimism, their patent refusal to be affected by all the little sadnesses of the day, is catching. So divinely inspired is this obstinate belief that it works like a tonic on the senses. They seem to be more than waitresses, more than women, even– they are perhaps divine. On a visit to The Waffle House I took with a friend, we were taken care of by a waitress who looked no older than 25. I remarked that she seemed young compared to many Waffle House waitresses. My friend, one of the last in the dying breed of laconic southern men, tilted his head to the side and said with a sagely air, “She’s replaced an angel that got her wings.”

The drinks arrive almost instantly, the orders taken with extreme efficiency. These interactions are punctuated by “darlin’”s and “sweetheart”s, of course. Above the kitchen din the order is shouted to the cook in a voice that sounds like a mother’s as she calls her children in for supper. No matter how loud or how high, it is a call our bones know, and so is soothing.

At this point, a patron will no longer be required to make any decisions, and so conversation will resume. If alone (or, I suppose, perhaps if accompanied), one may begin to look about the Waffle House at the other patrons. Besides the truckers ever-present at the bar, there will be an older couple tucked away in a corner booth, a few blue-collar workers eating alone on their lunch breaks, and in more recent years, a few ironic peacock-haired teenagers putting money in the jukebox. I have never once seen any patron speak to a group they did not come in with. This is a place one can be alone, or be alone with friends. The atmosphere has a somehow hampering effect on the feeling of being in a communal space, much like one feels when seated in a chapel on a weekday. All present have made their pilgrimage in the hope of finding something that speaking to strangers would simply get in the way of. That said, the presence of others seeking the same thing two pews or two booths over is a comfort. Here it is clear we are not alone in our needs, whatever they may be. There are always others. The Waffle House may sometimes be empty, but one never sees it this way. Such is the paradox of all holy places.

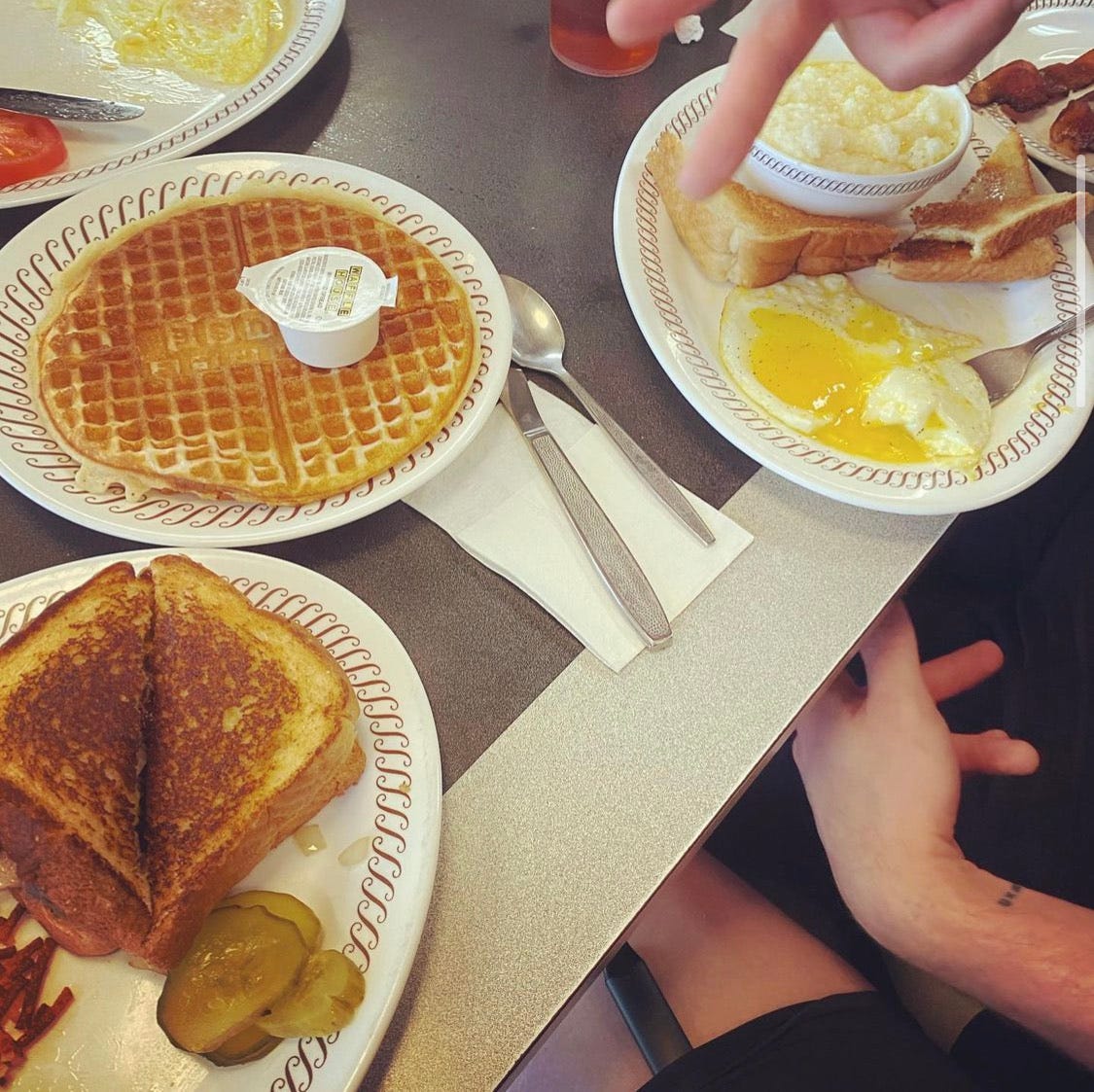

When the food arrives it is exactly as ordered. It is hot, steaming, straight off the griddle. Despite the heat, it is edible the moment the plate hits the table and needs no time to cool off. Just as the manna from heaven was edible as it fell, so too is this meal prepared by holy hands and delivered by angels-in-waiting. The patron is offered all kinds of condiments, several types of syrup, and butter. I often order raisin toast and have sometimes made the mistake of asking for butter to go with it. Without fail the waitress, with a twinkle in her eye both patient and teasing, will say, “Oh, just flip the bread.” Upon hearing this I already know the jig, remember the age-old song and dance. I flip the top triangle of toast, stacked so perfectly upon its brother. There is always butter under the toast. Always.

Some call it heresy to order anything at The Waffle House that does not fall into the category of American breakfast foods. I respectfully dissent, though I will concede that it is the tiniest bit blasphemous to stray from the Waffle House’s best offerings until one is fully baptized into its menu. One ought to have tried all the dishes at least once (this includes having their hashbrowns smothered, covered, chunked, diced, peppered, and capped) before calling themselves a believer. The food is wonderful, but the food isn’t even the most important offering. No one drags themselves to church on Sunday for the communion wafers. Neither does one haul their hungry, road-wearied, and hungover carcasses into The Waffle House for the waffles.

Once full and sated, the patron will take their little yellow ticket (delivered quietly only moments after the food arrived) to the register. Even in the modern era, the cash register isn’t digital. The waitress will do the math in her head, punching the items into the machine to formulate a total. It seems far less than it should be. In this year of our Lord two thousand and twenty-two the All-Star Special still rings up at a humble seven dollars and fifty cents. It’s the best bang-for-your-buck deal any American has gotten since the Louisiana Purchase.

It is nigh on impossible to leave The Waffle House without feeling some kind of stomach upset, either that one has eaten too much or has a bit of gas. Just as one might leave the Grand Canyon wondering at the colossal forces that formed it, so too does the pilgrim leave The Waffle House pondering what it all means. Of all the breakfast joints in all the towns in all the world, you wandered into the Waffle House.

As one and (all their fellow travelers) load up into their luxury car, their sensible sedan, or their hooptie, the magic will already be waning. Like the mist of a dream disperses as one wipes the sleep from their eyes, so too will fade the high definition clarity of your experience, the sharpness of your recollection. The details will dim until what’s left is the fuzzy haze of archetype and the dull plot points of memory. As one turns the ignition and steers themselves back onto the interstate, the main drag of town, or the back streets, the yellow sign will catch their eye in the rearview. One may wonder, only a few minutes out, “Just what was that, anyway?” One never vows to return and will not be thinking of the next visit. But that’s alright. Like all the truly great wonders of the world, The Waffle House never closes, never changes, never sleeps. It waits, steadfast as any ancient, and it waits for you.

Thanks for reading. To support me, consider buying my book of poetry, Control Burn, here:

Available in Paperback and on Kindle: https://amazon.com/dp/B0B37W546N/

Available on Gumroad as an ebook: https://darbradawn.gumroad.com/l/controlburn

Available as an ebook on Apple, Nook, Kobo, Scribd, Talia, Vivlio, Angus & Robertson: https://books2read.com/u/b5lJPR